A Modern California Dream, Still Haunted by Hippie Darkness

THORN TREE, by Max Ludington

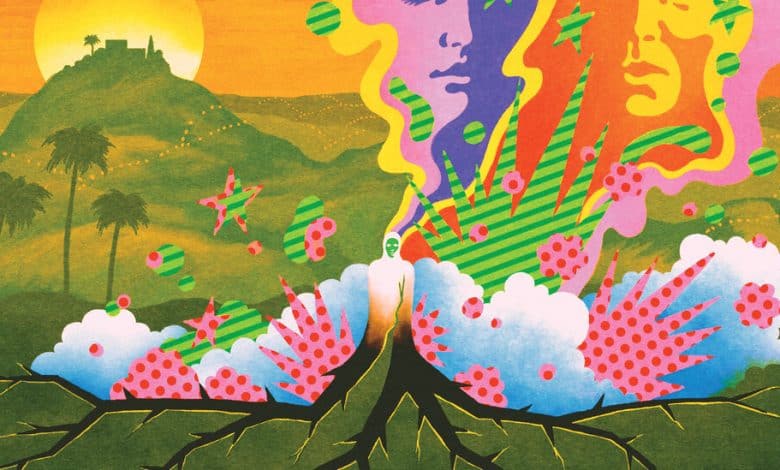

For every idyllic image of the 1960s there exists its dark inverse, a symbol of menacing chaos. Give me your flower crowns at Woodstock, your free love in Haight-Ashbury, and I’ll hand you the murdering Manson family, or the 5-year-old in Joan Didion’s “Slouching Toward Bethlehem,” high on the LSD her mother gave her. This slippage of the utopian into the dystopian lies at the heart of “Thorn Tree,” Max Ludington’s ominous second novel.

It’s 2017, and Daniel Tunison lives alone in the Beverly Hills guesthouse he inherited from his friend Cam. Daniel, 68, is a retired schoolteacher with an adult son he rarely sees, and, to make the most of his days, he’s a volunteer tutor at an after-school program. He leads a quiet, prescribed life, but the new occupants of Cam’s mansion are about to upend his careful existence.

Celia Dressler, “a young movie star fresh out of rehab number two and a round of tabloid thrashings,” nowlives in that house up the hill with her son, a first-grader named Dean, and her father, Jack. When the novel begins, she is in Arizona shooting an epic film and Jack is taking care of Dean. Or he should be. From the start, it’s clear that Jack, visiting Daniel one evening with a bottle of whiskey and a slew of prodding questions, isn’t to be trusted. He wants more from his neighbor than Daniel can imagine.

The novel skips around through multiple characters and time frames, asking us to make connections and comparisons, to note how the past persists in the present. We visit Celia on the set of a “surrealist, sci-fi ‘Anna Karenina’ reboot,” which she hopes will reinvigorate her career, and help keep her sober.

Then we swing back to Daniel in art school in 1968, when he meets and falls in love with a woman named Rachel. Rachel’s sudden death, following the couple’s first LSD trip at a Grateful Dead show, alters the course of Daniel’s life. It’s Rachel’s death that the novel swirls around, a traumatic event that will, decades later, bind Daniel to Jack. It also explains Daniel’s past as a famous outsider artist. While the descriptions of late-1960s drug use and Northern Californian commune life are terrifically vivid, the most remarkable passages in Ludington’s novel describe what drives Daniel, in the mid-1970s, to construct a massive tree from scrap metal. At first, he doesn’t understand his impulse to create; it begins with a “a pinhole in his gloom — distant, but real.”

Over time, his art becomes a way to negotiate his grief and confusion regarding the loss of Rachel. If building his tree can’t translate and rid him of his pain, then the act at least makes his life bearable, and legible. “Each design on each leaf seemed to exorcise an individual thought,” Ludington writes, “thoughts that could now go straight from his subconscious to the chisel without troubling his conscious mind.” There are multiple instances in “Thorn Tree” where art is offered as a conduit to — or toward — revelation, connection, purity. Art can expunge what Celia calls the “core fear” inside.