Lawsuits Over Tragedies Can Drag On. Not in the Florida Condo Collapse.

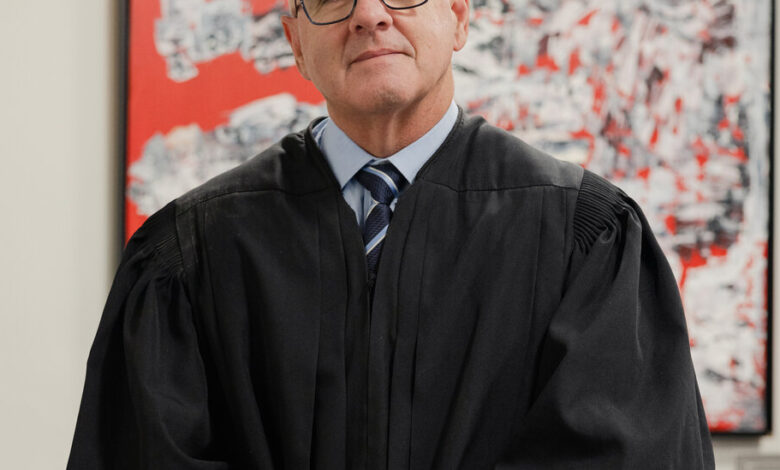

MIAMI — Each day, before the unusual hearings unfolded inside Judge Michael A. Hanzman’s Miami courtroom this summer, the judge’s aides would stock the judge’s bench, the lawyers’ tables and the witness stand with boxes of tissues. At some point, they knew, almost everyone would cry, and each excruciating presentation would end with Judge Hanzman offering people hugs.

The hearings in the civil case over the deadly collapse last year of a beachfront condominium tower in Surfside, Fla., gave survivors and victims’ families a chance to seek financial compensation for their enormous losses. But those involved in the proceedings also describe them as far more meaningful — something akin to catharsis — which they credit to the extraordinary handling of a case born out of calamity.

After five weeks of lengthy and emotional hearings, the court issued letters in late August, informing survivors and victims’ families of how much they would receive in damages from a settlement of more than $1 billion with insurance companies, the developers of an adjacent building and other defendants. Individual awards ranged from $50,000 for some post-traumatic stress disorder claims to more than $30 million for some wrongful death claims, Judge Hanzman said in an interview this week.

“I don’t think I have shed as many tears in my 61 years as much as I have throughout the last five weeks,” he said.

The collapse killed 98 people and left 135 unit owners dispossessed. There was no public fund like the one created for the victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Lawyers braced their clients for years of litigation, but instead, the Surfside checks are expected to be cut by the end of September, just 15 months after part of the Champlain Towers South came crashing down.

In a country with no shortage of plaintiffs or disasters, the story of the Surfside case and the people who brought it swiftly and sensitively to near its close could serve as a model for how the justice system treats and compensates victims in the future. Judge Hanzman said he has already fielded requests to speak about the case at legal seminars.

South Florida Urban Search and Rescue personnel sifting through rubble at the collapse site in June 2021.Credit…Angel Valentin for The New York Times

“Of everything bad that happened, this was the positive thing,” Elena Pazos, who lost her 23-year-old daughter, Michelle, and 55-year-old husband, Miguel, in the collapse, said in an interview.

She flew to Miami from her home in Montreal for the unusual closed-door claims hearings, which she said were handled with friendliness and understanding. The judge knew everyone by name.

“It made it so much easier than it would be otherwise to go through the legal system,” she said. “Emotionally, we are all brokenhearted people.”

There was no clear playbook to follow. In retrospect, the success of the Surfside case required willpower, experience, teamwork and sheer luck — beginning with Judge Hanzman, one of two judges in the complex business litigation division of the Miami-Dade County Circuit Court, being assigned by chance to the Surfside case.

At the start, he sought the counsel of Kenneth R. Feinberg, the special master for the 9/11 victims fund, and knew he did not want the case to drag on for years. Judge Hanzman declared that the Surfside matter would not be “business as usual,” and warned the lawyers involved that he would set a demanding schedule and not grant continuances or other legal motions that could lead to delays.

At one point during the case, Judge Hanzman had to relocate his chambers and courtroom, after an inspection of Miami’s civil courthouse found a litany of issues with the building and prompted its temporary closure.

His first unorthodox move was to persuade the surviving members of the Champlain Towers South condo association board to appoint Michael I. Goldberg, a lawyer, as an independent party known as a receiver to handle residents’ lawsuits. That allowed the judge to corral all of the complaints and eventually have them combined into one big lawsuit. Otherwise, there would probably have been dozens of separate legal actions.

Judge Hanzman chose well-known law firms to represent the plaintiffs, though the firms knew up front that there might not be enough money recovered to pay them. Some firms turned him down, the judge said.

The legal process was not without some friction. Even before all of the victims’ remains had been found in the rubble, the judge decided that the land where Champlain Towers South had stood would be sold, to ensure the biggest possible payout. Some families wanted a memorial built there instead of selling the land for redevelopment, but the judge concluded that a fund made up of insurance proceeds alone would fall far short of adequate compensation for the victims. The nearly two-acre property was sold to a Dubai-based developer in August for $120 million.

Next, Judge Hanzman dealt with conflicts between victims’ families, who had lost loved ones, and survivors, who had lost property. He persuaded Bruce W. Greer, a renowned mediator, to try to resolve their conflicts over how much money each group deserved to receive. In February, the condo unit owners agreed to split $83 million from the land sale and from Champlain Towers South’s insurers, a total that later went up to $96 million and paid them for the appraised value of their units.

Then Mr. Greer negotiated a second settlement: more than $1 billion to be shared among families who lost loved ones in the condo collapse. That sum that came from the developers, engineering consultants and security companies whom the law firms had identified as possibly at fault for the disaster, as well as their insurers. Federal investigators have still not determined the cause of the collapse.

Finally, Judge Hanzman and a retired judge, Jonathan T. Colby, a friend of 30 years, became the arbiters of how much each victim’s lost earnings — and their family’s pain and suffering — were worth.

They did not rely on any formula. Instead, they hired an accountant to assist with economic valuations and scheduled several three-hour hearings a day. They considered each victim’s age, occupation and potential lifetime earnings, as well as intangibles about how survivors have coped since their loved one’s death. Judge Colby called it “personalized justice.”

At their hearing, the Spiegel family shared photos and played video testimonials about their matriarch, Judy, who baked homemade mini waffles for her granddaughter Scarlett and went with her son Josh to several Paul McCartney concerts.

The judges “had a firm understanding of who we were and why we were there, and it made us feel comfortable to continue to open up and share stories,” said Rachel Spiegel, Judy’s daughter. “This was very personal.”

The Surfside case “should be used as a model for other cases,” said Kevin M. Spiegel, Judy’s husband. “That could minimize the pain and suffering.”

Two of their lawyers, Rachel W. Furst and Alex Arteaga-Gomez, said they admired that the hearings focused more on the victims than on the money — and that the settlement saved their clients from grinding lawsuits.

“We’re always representing people who are going through the worst experience of their life,” Ms. Furst said. “But the emotional experience of these damages hearings is much different than a deposition.”

Not everyone went through a hearing. Some victims’ families chose to forgo the process and accept a $1 million payout instead. Inevitably, some families received far bigger awards than others, though the individual awards will not be made public.

Under state law, not all relatives of victims were eligible for compensation. Judge Hanzman said he was heartened by how many people asked for the court to consider awards for extended family members like stepsiblings and in-laws.

“We just saw repeated acts of compassion and kindness and concern by these people that were in their darkest hour,” he said.

Many times, Judge Hanzman’s grand plan could have fallen apart. But he credited the lawyers for both the plaintiffs and the third-party defendants for working together, as well as Mr. Greer, Judge Colby and Mr. Goldberg for devoting themselves to the case.

Mr. Greer declined to be paid for his months of difficult work, even after Judge Hanzman tried to cover a portion of his fee. Judge Colby, who also worked free of charge, traveled to Miami for the claims hearings a few days after his mother’s death.

Mr. Goldberg collapsed from apparent exhaustion in April and spent two days in the hospital.

“When I’m 85, sitting in a nursing home, and nobody wants to listen to me, this is certainly the case that I’m going to tell them about,” Mr. Goldberg said in an interview. “This is the mantel on a lot of our careers, including the judge’s.”

Everyone involved, without fail, commended Judge Hanzman for designing the structure of the case and setting its tone and pace.

He allowed survivors and victims’ families to speak at every hearing and delivered hard truths in a way that was both unvarnished and empathetic. Through it all, he still juggled a docket of about 250 other cases.

Judge Hanzman grew up in Winter Park, Fla., near Orlando. He did not know any lawyers personally as a child, but he noticed that when lawyers came to his father’s small gas station, they drove nice cars. After graduating from law school at the University of Florida, he made millions of dollars a year as a highly successful commercial litigator.

He sought a career change after turning 50, and gave up his lucrative practice after Gov. Rick Scott, a Republican, appointed him to the bench in 2011. His first assignment was in juvenile dependency court, a post that typically lasts a short time. He found it so fulfilling that he stayed for five years.

Before Surfside, his courtroom made perhaps the most headlines when the pants pocket of an accused arsonist’s lawyer caught fire during trial. Now, the judge is often stopped in restaurants, the grocery store and the golf course by people who recognize him.

He decided to conduct the claims hearings himself — as opposed to delegating them to an outsider — because the families deserved that attention, he said, despite knowing that the process would exact an emotional toll.

He dabbed his eyes once again at a hearing on Monday to decide the attorneys’ fees — this time, because the families and lawyers who packed his courtroom gave him a standing ovation.