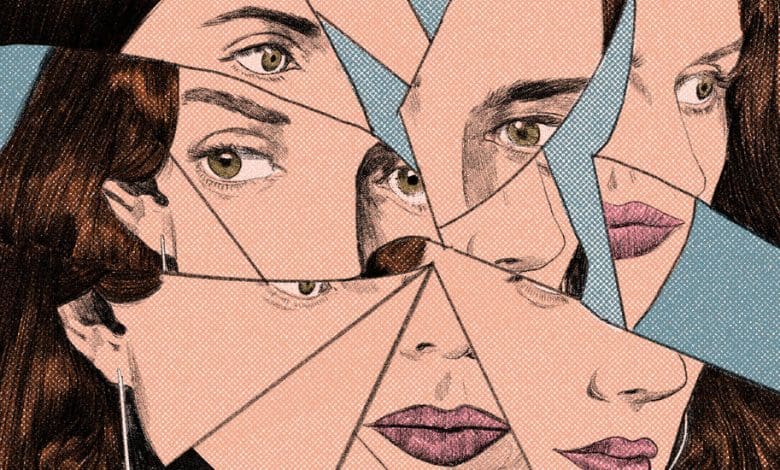

Writer, Mother, Ex-Wife: Leslie Jamison Is a Self in ‘Splinters’

SPLINTERS: Another Kind of Love Story, by Leslie Jamison

We live in a golden age of autobiographical women’s writing. Real equality in publishing is still elusive, but the straight male inner world that was so meticulously, relentlessly documented in prizewinning books of the past century, from Roth to Styron to Ford, has been forced at last from its position of unchallenged supremacy. In its place has arisen a group of brilliant women, inclusive of trans women, with their own ideas for the form, among them Maggie Nelson, Eula Biss, Valeria Luiselli, Margo Jefferson, Alison Bechdel, Rachel Cusk, Carina Chocano — and Leslie Jamison.

Jamison, now 40, is the author of a new memoir called “Splinters.” It tells the story of her divorce and first years as a single mother. In her previous books, the finest of which remains “The Empathy Exams” (2014), Jamison often used hybrid forms, crossing autobiography with journalism and essays; in “Splinters,” however, as if the urgency of motherhood has retired the need for those inflecting techniques, she tells her tale straightforwardly.

Nevertheless, her true subject has stayed intact: the tormented ambiguity of all action, ethical and aesthetic and personal, and the consequent divisions of the self, what Virginia Woolf called the “butterfly shades” of consciousness. “One piece of me said, It’s unbearable,” Jamison writes about being apart from her baby. “The other piece said, It’s fine. Both pieces were lying. Nothing was fine, and nothing was unbearable.”

As “Splinters” begins, Jamison and her husband, “C,” are in the initial stages of their separation: “At drop-offs, as I stood with the baby in the stroller beside me, he called from the vestibule, Why don’t you eat something, you anorexic bitch. Or he said, Don’t you [expletive] talk to me. When I said, Please don’t speak to me like that, he leaned closer to say, I can speak to you however I [expletive] want.” In another drop-off scene he spits at her.

This is bitter proof of how monstrous love can turn. But Jamison, whose powerful mind is geared toward dialectic, finds as ballast for that injury an immense, nuanced, often physical hope in her newborn daughter. “Sometimes I felt the baby belonged to me absolutely,” she writes. “Sometimes when she lay sleeping beside me in her bassinet, I ran my fingers along my scar in the darkness: the thick stitches, the shelf of skin above like an overhang of rock. It was just a slit that led to my own insides, but it felt like a gateway to another world. The place she’d come from.”

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.