This Judge Is Blind. He Wishes Our Justice System Were, Too.

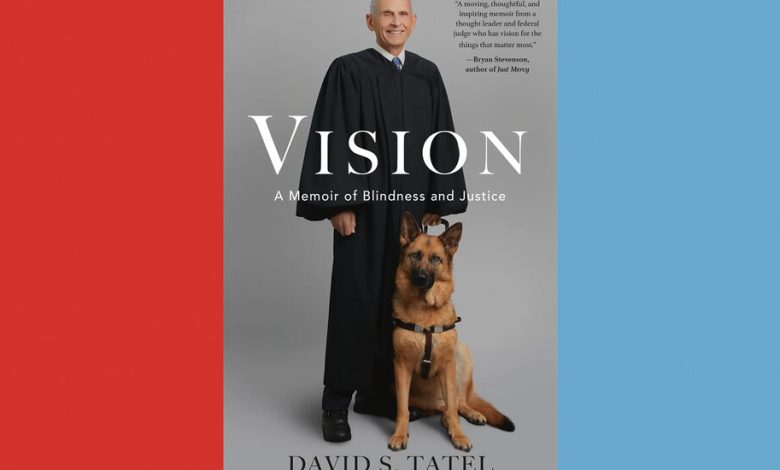

VISION: A Memoir of Blindness and Justice, by David S. Tatel

On the evening of July 13, 2020, Judge David S. Tatel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit — the country’s second most powerful court — was exchanging frantic messages with colleagues.

That afternoon, Indiana prison officials had planned to inject Daniel Lewis Lee, a convicted murderer, with a massive dose of pentobarbital. But Lee’s lawyers, arguing that the drug could cause his lungs to fill with fluid and make him feel as if he were drowning, had persuaded a lower court to suspend the execution on the grounds that it might violate the Constitution’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishments.”

Eager to see the execution proceed, President Donald Trump’s Justice Department had appealed to the D.C. Circuit. As with all his rulings, Judge Tatel was ready to issue his decision without having laid eyes on the lower court opinion, briefs or other relevant documents. This is because he is blind.

Tatel, now 82 and recently retired, has had a remarkable career: as a civil rights lawyer, champion of equal opportunity and federal judge. He succeeded Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the D.C. Circuit and would probably be on the Supreme Court today were it not for Bush v. Gore, which handed the presidency to George W. Bush (giving us Justices John Roberts and Samuel Alito instead).

For decades before he joined the bench, Tatel fought for school integration, legal aid for the poor, Title IX, the environment, voting rights and more. For most of his career, he did so without the modern audio devices the visually impaired use today. Instead, he relied on primitive gadgets like a “Braille ’n Speak” computer, human readers and a prodigious memory.

Tatel was not always blind. As he recounts in his extraordinary memoir, “Vision,” he remembers the “Whites Only” signs in the shops near his childhood home in suburban D.C.; his high school’s basement shooting range (rifles, ammo and targets courtesy of the U.S. Army); the stars he could almost see through his father’s telescope. In 1954 — the year of Brown v. Board of Education, the addition of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance and his bar mitzvah preparations — a ball he couldn’t see hit him in the face. The doctors advised him to eat more carrots. Eventually, one diagnosed retinitis pigmentosa, which causes gradual vision loss.